Horses with a burr under their saddle

Girthiness is commonly associated with the consequences of tightening the girth too quickly when the saddle is first put on. But although there has been so much progress in the field of saddle making during the last decades and the awareness of the importance of saddle fitting and careful girthing has positively changed, many of our modern riding horses across all breeds are girthy. On reflection, this does not come as a surprise. What if the reason for the girthiness of a large part of the horses concerned were to be found in the low back position?

In former times, during the great wars and the military service regulations, the cavalry used solid, strong horses. As youngsters, they had to be fit for service as quickly as possible in order to carry the soldiers over long distances through fields, woods and meadows. Their movements were economical, enduring and energy-saving, their bodies compact and stable. The phase of getting used to the saddle and rider had to be short. The "horse material" needed to be ready for use quickly and reliably. Under the army saddle – usually a standard model – they used a military blanket made of pure wool to cushion the roughest fitting inaccuracies. Nevertheless, most cavalry horses exhibited signs of ill-fitting saddles and became girthy, which was considered an acceptable collateral damage.

Many things have changed since then. The range of saddle models, pads and girths is almost unmanageable today, the anatomical shape and the generous freedom of the shoulder are now part and parcel of every equestrian discipline. Nevertheless, a large number of horses still express their discomfort under the saddle with girthiness! How can that be?

The answer to this question lies in modern horse breeding, which today produces wonderful horses: willing to perform, sensitive, big movers. This extreme mobility (hypermobility), which we observe not only with warmbloods but with almost all breeds from Quarter horses to Iberian horses and Icelandic horses etc., also means that the connective tissue in the entire body is excessively elastic. This makes the entire body of the horse unstable and if the training is not adapted to these anatomical conditions and functional needs, this has fatal consequences because of the enormous thrust of the hindquarters.

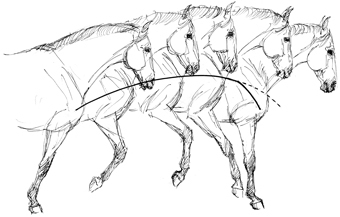

What does this have to do with girthiness? Unlike humans, horses do not have collarbones. Instead, the forelimbs are connected to the trunk by some sort of sling construction made of muscles, ligaments and tendons. These are all connective-tissue type structures that are now less stable than a few decades ago. If those modern horses with their enormous thrust are trained traditionally, i.e. without engagement through the back (see our paper "How to put backbone into horse training") and without straightening the horse, they push with huge thrust in this weak supporting structure, which is even worse if the rider’s weight is added. The longer this situation lasts, the deeper the trunk sinks. With some horses, the sternum is even clearly protruding, other start coughing because of this mechanical stimulus of the chest. The rib cage expands like a balloon because neither the arching top-line musculature nor the supporting abdominal and pectoral musculature stabilizes the trunk. Such horses are mistakenly considered fat and put on a diet, even though they actually need high-quality food in adequate quantity and most importantly efficient functional training to regain fitness.

Let’s come back to the girth: The lowest point where all the downward forces clash is the position of the girth. No matter how careful you fix the girth, it will produce uncomfortable pressure that can even become painful. In the beginning, this pressure only arises during riding sessions. However, by and by, this pain is associated with the tack item itself. We must not forget that horses that exhibit such a movement pattern and conformation are not straightened. This means that the saddle cannot be functionally fitted. Instead, saddle fitters adapt the saddles to the crookedness of the horse and major shortcomings in the horse’s body are at most concealed with corrective pads. However, this kind of saddle fitting can only offer temporary relief to the horse and is not a sustainable solution.

This kind of girthiness that is inherent to the conformation of the horse or caused by inadequate training can only be eliminated with functional straightness training. The horse must learn how to transform thrust into load-bearing capacity, at first without saddle and rider weight. Only after achieving this essential training step, we should put a fitted saddle on the horse’s back and fix it carefully with a generously cushioned girth. We must not forget that for the reasons given above, it is not enough to cushion only the lowest point of the girth on the sternum. The entire girth must be softly padded along the rib cage area. With this equipment, the training can continue – still without a rider on the horse’s back – until the horse has regained confidence in the girth that now is not restrictive anymore thanks to the new biomechanics of the horse. Only now that the horse is able to transform its overflowing thrust into load-bearing capacity, able to relief the entire supporting apparatus thanks to the biomechanics of the athlete, we can add a rider.

This entire process can take several weeks or even month. Girthiness is a serious trauma in the body that the horse has to overcome physically and psychologically.

In order to help girthy horses even more, the ARR Center for Anatomically Correct Horsemanship has developed a purpose-built girth. We are currently discussing its commercial manufacturing. We will keep you informed and give you more detail in due time. Nevertheless, we also cherish well-tried traditional equipment: We still like to use woolen army blankets to protect the backs of our training horses under the saddle. However, the best equipment is not worth anything if we do not adapt the training in order to show the horse how to switch its biomechanics from a fear and flight response to athletic movement patterns. This is the only way to make sure that we do not only treat symptoms, but work up sustainable solution for health-preserving equestrian sport.